INDIRA RAHMAN

"It wasn’t that I rejected Bangladesh. It was that from the moment I was born, Bangladesh rejected me and people like myself."

Summer Of 2015

The summer of 2015 I worked as an assistant at a law firm. It was Kamal Hossain & Associates. One afternoon I came across a book on human rights law and the Constitution. And you know, I came across Section 377, and that was pretty awful. It really ruined my summer. It's because already after going back that summer I could feel something was different because I was so accustomed to just being out at that point... out as a bisexual non-binary person... I was also out particularly about my views on women's rights, my views on religion, especially my views on a number of societal issues that caused a lot of tension with my family, but also my nonprofit co-workers. Because you know, they would say, ‘you don't seem like yourself’, ‘you seem very different’, or ‘you've changed’. And internally I was like, ‘yeah, it's not like I have changed. This is how I've always been. I was just never very out about it.’ And I'm still not fully out about some of the more crucial aspects of myself. That's why that summer, coming across Section 377 was... It was a shift in world view. It really was because I had evidence of societal marginalization and persecution. But then this [persecution] was kind of legal. This was criminalization of people like myself. And it felt unjust. It felt unfair. I was angry because I was working at the law firm Kamal Hossain & Associates and the moniker comes from one of the most prominent writers of the Constitution [of Bangladesh]. And I was like, ‘yeah, I know the 1970s weren't a great time, but did you think about what you were leaving in the criminal justice code?’

২০১৫ সালের সামারে আমি কামাল এন্ড এসোসিয়েটস নামে একটা ল’ ফার্মে সহকারী হিসেবে কাজ করতাম। একদিন বিকালে আমি মানবাধিকার আইন বিষয়ক একটা বই ও সংবিধান পড়ছিলাম। এবং যখন সংবিধানের ৩৭৭ ধারাটা আমার সামনে পড়লো, সেটা দেখে মানসিকভাবে খুব বাজে লাগছিল। আমার পুরা সামারটাই মাটি হয়ে গেল। এমনিতেও দেশে ফিরে ঐ সামারে মনে হচ্ছিল কি যেন আগের মতো নেই। কারণ ততদিনে আমি দেশের বাইরে নিজেকে খোলামেলা ভাবে প্ৰকাশে অভ্যস্ত হয়ে গেছি। সেখানে আমি নিজেকে বাইসেক্সচুয়াল নন বাইনারি হিসেবে পরিচয় দেই। এছাড়াও আমি নারী অধিকার, ধর্ম সম্পর্কে আমার দৃষ্টীভঙ্গি, বিশেষ করে বিভিন্ন সামাজিক বিষয় সম্পর্কে আমার চিন্তাগুলো খোলামেলাভাবেই প্রকাশ করতাম। যে কারণে আমার পরিবার এবং নন প্রফিট সহকর্মীদের সাথে অনেক টেনশন তৈরি হচ্ছিল। কারণ জানো, তারা বলত, “তোমাকে ঠিক তোমার মত লাগছে না”, “তোমাকে ভিন্ন রকম লাগছে”, বা “তুমি বদলে গেছো”। এর জবাবে আমি ভিতরে ভিতরে ভাবতাম, “আমি বদলায়নি, আমি সবসময় এমনই ছিলাম, খালি আগে প্রকাশ করিনি।” আমার চিন্তার আরো কিছু গুরুত্বপূর্ন দিক আছে যেগুলার ব্যাপারে আমি এখনো পুরাপুরি আউট না। ঐ সামারে ৩৭৭ ধারার মুখোমুখি হওয়ার পরে... আমার দুনিয়া নিয়ে চিন্তা ভাবনাই বদলে গেছে। মানে আমি সামাজিক বৈষম্য আর নিপীড়নের ব্যাপারে জানতাম, কিন্তু সমকামীদের উপর এই অত্যাচারের স্বীকৃতি তো রাষ্ট্রই দিয়ে রেখেছে। এমন একটা আইন যেটা দিয়ে আমার মতো মানুষকে ক্রিমিনালাইজ করে রাখা হয়েছে। এটাকে খুব অন্যায়, অন্যায্য মনে হচ্ছিলো। আমার খুব রাগ লাগছিল যে আমি কামাল হোসেন এন্ড এসোসিয়েটসে কাজ করি। কামাল হোসেন বাংলাদেশ সংবিধানের অন্যতম একজন লেখক এবং তার কাছ থেকেই এই আইন এসেছে। আমি জানি ১৯৭০ এর সময়টা রাজনৈতিকভাবে খুব অস্থীতিশীল ছিল, কিন্তু কামাল হোসেন কি কখনো ভেবেছেন তিনি ফৌজদারি বিচারব্যবস্থায় কি (ভয়ঙ্কর আইন) রেখে যাচ্ছেন ?

Summer Of 2016

Every year in late April, it's like clockwork. It comes back like a nightmare, right? Xulhaz and Tonoy, the murders. I was here in the U.S. across the pond, so to speak, when it happened. But I remember how awful social media was. I mean, even from across the pond, I had a reaction to it. The amount of victim blaming, the amount of comments saying that ‘this [homosexuality] is against Islam’, ‘they [vigilantes] won't kill Muslims and they [Xulhaz and Tonoy] deserve what happened to them’ or ‘if they [Xulhaz and Tonoy] didn't want to die, then they shouldn't have offended public sensibilities’. This was me experiencing it second hand and that was pretty traumatic. So I can't imagine what it was like for the community that was in Bangladesh! And so while I was reading the comments, experiencing it via social media from across the pond, at that point I had only known societal marginalization. I had an inkling of how taboo it was, right? But this was confirmation of a nightmare that I didn't even think I was supposed to have, right? And by that I mean, having grown up in Bangladesh, I was already aware of this societal persecution. But it was a confirmation that any possibility of a future in Bangladesh was... It wasn't possible. And the after effects from across the pond were just, oh my god, I couldn't confide in anyone. I didn't go to counseling at that point. I think I was really listless. I was drifting through the rest of my semester at that point because I was like, you know what? What does it matter what I do here when something this big, something like this that you can’t take back has happened in Bangladesh? And then the semester after, it was a slow boiling point. I always had a lot of repressed anxiety and depression, just a lot of trauma from having to always censor myself in Bangladesh, keeping a lot of things inside. You know, after the summer of 2016, I just kind of reached a boiling point over the next semester, over the next six, seven, eight months, just random panic attacks, a complete breakdown in December of 2016. Because I felt like I had been completely rejected from Bangladeshi society because I didn't see a place in it, and I didn't know what to do with that realization. It was a weird out of body experience. Because I was experiencing it in a completely different cultural context in the U.S. With the knowledge that after I got my degrees, I would have to go back to Bangladesh. I think that was part of my anxiety.

প্রতিবছর এপ্রিল মাসের শেষটা যেনো ঘড়ির কাঁটার মত ঘুরে আসে। একটা দুঃস্বপ্নের মত ফিরে আসে, রাইট? জুলহাজ ও তনয়ের খুন। ওরা যখন খুন হয় আমি এখানে আমেরিকাতে ছিলাম। আমার মনে আছে সোশ্যাল মিডিয়ায় কি পরিমাণ বাজে প্রতিক্রিয়া দেখা গেছে। মানে, এখানে আমারিকায় এত দূরে বসেও আমার এগুলার প্রতি রিএকশ্ন হইছে। ভিক্টিম ব্লেমিং এর পরিমাণ, ‘হোমোসেক্সুয়ালিটি ইসলাম বিরোধী’ এমন কথা বলা কমেন্টের পরিমান, ‘তারা কোনো মুসলমানকে হত্যা করবে না এবং তাদের [জুলহাজ এবং তনয়] যা হয়েছে সেটা তারা ডিজার্ভ করে', বা ‘তারা [জুলহাজ এবং তনয়] যদি মরতে না চাইতো তাহলে তাদের পাবলিক সেন্সিবিলিটিতে আঘাত না করলেই হত’। মানে, এরকমই ছিল, আমি দূর থেকে এগুলা এক্সপেরিয়েন্স করছিলাম যেটা খুবই ট্রমাটিক ছিল। বাংলাদেশি কমিউনিটির জন্য এটা কেমন ছিল তা আমি চিন্তাও করতে পারি না! আমি যখন এইসব কমেন্ট পড়ছিলাম আর সোশ্যাল মিডিয়ার মাধ্যমে পুরো জিনিসটা এক্সপেরিয়েন্স করছিলাম, একটা পর্যায়ে আমি ভাবলাম, অতীতে আমি এই কমিউনিটির মানুষদের কেবল সামাজিক মার্জিনালাইজেশন সম্পর্কে কিছুটা জানতাম। আবার সামাজিকভাবে হোমসেক্সুয়ালিটিকে কতটা ট্যাবু হিসেবে দেখা হয় তা নিয়াও কিছুটা ধারণা ছিল। কিন্তু এই হত্যাকান্ড একটা জলজ্যান্ত দুঃস্বপ্নের কনফার্মেশন ছিল যার কথা আমি ঘুণাক্ষরেও ভাবি নাই, রাইট? মানে, আমি যেহেতু বাংলাদেশে বড় হইছি, আমি সেখানকার সামাজিক অত্যাচারের কথা জানতাম। কিন্তু এই হত্যাকান্ডের পরে বুঝে গেলাম বাংলাদেশে আমার আর কোনো ভবিষ্যৎ নেই। আমি আর কাউকে বিশ্বাস করতে পারছিলাম না। আমি তখন কোথাও কাউন্সেলিং করাতেও যাই না। আমি পুরা লিস্টলেস হয়ে গেছিলাম, কি করবো তাই জানি না। পুরা সেমিস্টার জুড়ে আমি যেন ভেসে বেড়াচ্ছিলাম, একটা পর্যায়ে আমি কি ভাবছিলাম জানো? এসবের কি মূল্য আছে? আমি এখানে যাই করি না কেন তার কি মূল্য আছে যখনএমন একটা বিশাল বড় ঘটনা বাংলাদেশে ঘটে গেছে। এবং ঐ সেমিস্টারের পরে, এটা একটা স্লো বয়েলিং পয়েন্ট ছিল। আমার সব সময়েই চাপা এংজাইটি ও ডিপ্রেশন ছিল, যেহেতু বাংলাদেশে নিজেকে সবসময় সেন্সর করে চলতে হত ফলে নিজের মধ্যে অনেক ট্রমা জমা হয়েছিল। জানো, ২০১৬-র ঐ গরমকালের পরে, আমি একটা বয়েলিং পয়েন্টে পৌছে যাই, আমার পরবর্তী সেমিস্টারের পুরাটা, তার পরের, ছয়, সাত, আট মাসে র্যান্ডমলি প্যানিক এট্যাক হত, ২০১৬-র ডিসেম্বরে একটা কমপ্লিট ব্রেকডাউন হল। কারন ফিল হইছিল যে, বাংলাদেশের সমাজ থেকে আমি পুরাপুরি রিজেক্ট হয়ে গেছি। আমি এর মধ্যে আমার জন্য আর কোনো জায়গা দেখতে পাচ্ছিলাম না। আমি জানতাম না এই উপলব্ধি নিয়ে আমি কি করবো। এটা একটা অদ্ভুত আউট অফ বডি অভিজ্ঞতা ছিল। কারণ আমি এটা বংলাদেশ থেকে অনেক দূরে একদমই ভিন্ন কালচারাল কনটেক্সটে এক্সপেরিয়েন্স করতেছিলাম। আমি জানতাম যে ডিগ্রী পাওয়ার পরে আমাকে বাংলাদেশে ফিরে যেতে হবে। আমার মনে হয় ঐটা আমার এংজাইটির একটা অংশ ছিল।

I Never Had A Relationship With Bangladesh

Efad: At present, how do you think of your relationship to Bangladesh?

Indira: What relationship? (laughter) I mean, it would feel like a breakup, but we never had a relationship to begin with. Like, from the moment I was born, I was criminalized in this country. Can you imagine being born criminalized? Isn't that such a weird concept? Like, how can you criminalize people for things that they have no control over, for actions or things that they haven't done? You are just automatically a criminal in the eye of the state from the moment you take your first breath. That is… That is absurd. So it wasn't that I rejected Bangladesh. It was that from the moment I was born, it rejected me and people like myself. I always had a complicated relationship with Bangladesh when growing up. Bangladesh is majority Muslim. And you know, it’s like clockwork, it goes through periods of public opinion shifts—in favor of being a secular state versus being an Islamic state. Being an atheist, that was just heart-stoppingly scary. I had always known that I was an atheist. Like, yeah, my parents forced me to, you know, read the [holy] books. But I was like, ‘this is bullshit’. Like, why am I reading stuff that I don't understand in a language that I don't understand? So from a very early age I wasn't aware of how homosexuality is criminalized but I was aware of a lot of societal disparities. I was aware of how binary, how heteronormative, how gendered Bangladeshi society is. I never fit into that. You know how religious Bangladeshi society is. Like, you would have Friday sermons at mosques, blaring from the mikes. You don't have to broadcast it! Come on! It's freedom of religion and all that. But you don't have to broadcast how women are the primary residents of hell or whatever! A lot of sermonising is like that, a lot of toxic messaging around that… Even before all the issues with my gender identity and sexuality (sexual orientation became more important in my life mostly here in the U.S.), I always had a fraught relationship with religion because I never pretended to be anything but an atheist... And then you'll remember a spate of targeted societal persecution and murders of atheists, secularists, and bloggers in Bangladesh. I mean, it would be like clockwork, like every few months you would open the newspaper and you would see someone else have been murdered in broad daylight for offending Islamic sensibilities, and it wasn't just random murders. These bloggers were put on a list. There was organized action by the vigilantes who committed the murders. It was systematic. It was designed to provoke and inspire fear. It was designed to provoke and engender silence. So I felt like I was... I think that was one of the first times in my life where I was genuinely, just scared.

Indira: What relationship? (laughter) I mean, it would feel like a breakup, but we never had a relationship to begin with. Like, from the moment I was born, I was criminalized in this country. Can you imagine being born criminalized? Isn't that such a weird concept? Like, how can you criminalize people for things that they have no control over, for actions or things that they haven't done? You are just automatically a criminal in the eye of the state from the moment you take your first breath. That is… That is absurd. So it wasn't that I rejected Bangladesh. It was that from the moment I was born, it rejected me and people like myself. I always had a complicated relationship with Bangladesh when growing up. Bangladesh is majority Muslim. And you know, it’s like clockwork, it goes through periods of public opinion shifts—in favor of being a secular state versus being an Islamic state. Being an atheist, that was just heart-stoppingly scary. I had always known that I was an atheist. Like, yeah, my parents forced me to, you know, read the [holy] books. But I was like, ‘this is bullshit’. Like, why am I reading stuff that I don't understand in a language that I don't understand? So from a very early age I wasn't aware of how homosexuality is criminalized but I was aware of a lot of societal disparities. I was aware of how binary, how heteronormative, how gendered Bangladeshi society is. I never fit into that. You know how religious Bangladeshi society is. Like, you would have Friday sermons at mosques, blaring from the mikes. You don't have to broadcast it! Come on! It's freedom of religion and all that. But you don't have to broadcast how women are the primary residents of hell or whatever! A lot of sermonising is like that, a lot of toxic messaging around that… Even before all the issues with my gender identity and sexuality (sexual orientation became more important in my life mostly here in the U.S.), I always had a fraught relationship with religion because I never pretended to be anything but an atheist... And then you'll remember a spate of targeted societal persecution and murders of atheists, secularists, and bloggers in Bangladesh. I mean, it would be like clockwork, like every few months you would open the newspaper and you would see someone else have been murdered in broad daylight for offending Islamic sensibilities, and it wasn't just random murders. These bloggers were put on a list. There was organized action by the vigilantes who committed the murders. It was systematic. It was designed to provoke and inspire fear. It was designed to provoke and engender silence. So I felt like I was... I think that was one of the first times in my life where I was genuinely, just scared.

ইফাদঃ বর্তমানে তোমার সাথে বাংলাদেশের সম্পর্কটাকে কীভাবে দেখো?

ইন্দিরাঃ কিসের সম্পর্ক? (হাহা) মানে, যদি আমাদের মধ্যে কোনো সম্পর্ক থাকতো তাহলে এখন ব্রেক আপ হয়ে গেছে বলতে পারতাম। যে মুহুর্তে আমার জন্ম হয়েছে, তখন থেকেই বাংলাদেশে আমি অপরাধী। তুমি অপরাধী হিসেবে জন্ম নিয়েছো চিন্তা করতে পারো? এটা অদ্ভুত জিনিস না? যে জিনিসের উপর আমার নিজের কোনো নিয়ন্ত্রণ নেই বা যেটা আমি এখনো করিইনি সেটার জন্য আমি কিভাবে অপরাধী হতে পারি? প্রথম নিঃশ্বাসটা ফেলার সাথে সাথেই রাষ্ট্রের চোখে তুমি অপরাধী হয়ে গেলে, এটা এবসার্ড। এমন না যে আমি বাংলাদেশকে রিজেক্ট করেছিলাম। বরং আমার জন্মের মুহুর্ত থেকে বাংলাদেশ আমাকে এবং আমার মত মানুষদেরকে রিজেক্ট করেছিল। বাংলাদেশের সাথে আমার সম্পর্কটা সবসময়েই খুব জটিল। বাংলাদেশ একটা সংখ্যাগরিষ্ঠ মুসলিম দেশ। এবং তুমি জানো, এটা ঘড়ির কাঁটা ঘোরার মত, এক সময় জনগণ সেক্যুলার রাষ্ট্র চায় তো আরেক সময় ইসলামিক রাষ্ট্র। এরকম একটা জায়গায় নাস্তিক হওয়াটা একটা দমবন্ধ ভয়ের ব্যাপার। আমি সবসময়ই জানতাম যে আমি নাস্তিক। লাইক, হ্যাঁ, আমার বাবা-মা আমাকে ঐ [ধর্মীয়] বই পড়তে জোর করেছে, বলছে বইটা পড়ে দেখো, কিন্তু আমার কাছে অদ্ভুত লাগতো যে আমি এমন কিছু কেন পড়বো যার ভাষাই আমি বুঝি না। একদম ছোট থাকতে হোমোসেক্সুয়ালিটিকে যে বাংলাদেশে ক্রিমিনালাইজড করা ছিল তা আমি জানতাম না, কিন্তু অনেক ধরণের সামাজিক বৈষম্য সম্পর্কে বেশ সচেতন ছিলাম। বাংলাদেশের সমাজ কতটা বাইনারি, কতটা হেটোরোনরমাটিভ, কতটা লিঙ্গ বৈষম্যমূলক ছিল সেগুলা নিয়ে সচেতন ছিলাম। এবং এর মধ্যে ঠিক মানিয়ে নিতে পারিনি । তুমি জানো যে বাংলাদেশের সমাজ কতটা রিলিজিয়াস। যেমন, শুক্রবার দিনে খুতবার সময়ে মসজিদের মাইকগুলো যেনো ফেটে পড়ত। তোমার তো এভাবে প্রচার করার দরকার নাই! আচ্ছা, এটা যার যার ব্যক্তিগত ধর্মীয় স্বাধীনতা সেটা মানলাম, কিন্তু তোমার তো খুতবার মধ্যে এটা প্রচার করার দরকার নাই যে নারীরাই জাহান্নামের প্রথম বাসিন্দা, এরকম অনেক কিছু, অনেক টক্সিক কথাবার্তা বলা হত… আমার জেন্ডার আইডেন্টিটি এবং সেক্সুয়ালিটির (সেক্সুয়াল অরিয়েন্টশন আমার এখানকার আমেরিকার জীবনে এসে গুরুত্বপূর্ন হয়ে উঠছে) ইস্যু বাদেই ধর্মের সাথে আমার একটা বাজে সম্পর্ক ছিল কারন নিজেকে কখনো আমি নাস্তিক ছাড়া অন্য কিছু এমনটা ভাবিনি... এরপর, বাংলাদেশে নাস্তিক এবং সেক্যুলারিস্ট, ব্লগারদের উপর সামজিক নির্যাতন ও খুনের যে মহোৎসব শুরু হলো সেটা নিশ্চয়ই তোমার মনে আছে। এটাও ঘড়ির কাঁটা ঘোরার মতই ছিল, যেমন - কয়েক মাস পর পরই পত্রিকা খুললেই দেখবা যে কোনো একজনকে ইসলামী অনুভূতিতে আঘাত দিছে বলে প্রকাশ্য দিনের আলোয় খুন করা হইছে। এগুলা কিন্তু কোনো র্যান্ডম খুন ছিল না। এই ব্লগারদের নামের তালিকা করা হয়েছিল। এইগুলা খুনীদের প্ল্যান করে করা কাজ। এইগুলা সিস্টেমেটিক ছিল। একটা ভয় ছড়ানোর জন্যই এগুলার ডিজাইন করা হয়েছিল। এবং আমি... আমার মনে হয় জীবনে প্রথমবারের মত সত্যি অনেক ভয় পেয়েছিলাম।

ইন্দিরাঃ কিসের সম্পর্ক? (হাহা) মানে, যদি আমাদের মধ্যে কোনো সম্পর্ক থাকতো তাহলে এখন ব্রেক আপ হয়ে গেছে বলতে পারতাম। যে মুহুর্তে আমার জন্ম হয়েছে, তখন থেকেই বাংলাদেশে আমি অপরাধী। তুমি অপরাধী হিসেবে জন্ম নিয়েছো চিন্তা করতে পারো? এটা অদ্ভুত জিনিস না? যে জিনিসের উপর আমার নিজের কোনো নিয়ন্ত্রণ নেই বা যেটা আমি এখনো করিইনি সেটার জন্য আমি কিভাবে অপরাধী হতে পারি? প্রথম নিঃশ্বাসটা ফেলার সাথে সাথেই রাষ্ট্রের চোখে তুমি অপরাধী হয়ে গেলে, এটা এবসার্ড। এমন না যে আমি বাংলাদেশকে রিজেক্ট করেছিলাম। বরং আমার জন্মের মুহুর্ত থেকে বাংলাদেশ আমাকে এবং আমার মত মানুষদেরকে রিজেক্ট করেছিল। বাংলাদেশের সাথে আমার সম্পর্কটা সবসময়েই খুব জটিল। বাংলাদেশ একটা সংখ্যাগরিষ্ঠ মুসলিম দেশ। এবং তুমি জানো, এটা ঘড়ির কাঁটা ঘোরার মত, এক সময় জনগণ সেক্যুলার রাষ্ট্র চায় তো আরেক সময় ইসলামিক রাষ্ট্র। এরকম একটা জায়গায় নাস্তিক হওয়াটা একটা দমবন্ধ ভয়ের ব্যাপার। আমি সবসময়ই জানতাম যে আমি নাস্তিক। লাইক, হ্যাঁ, আমার বাবা-মা আমাকে ঐ [ধর্মীয়] বই পড়তে জোর করেছে, বলছে বইটা পড়ে দেখো, কিন্তু আমার কাছে অদ্ভুত লাগতো যে আমি এমন কিছু কেন পড়বো যার ভাষাই আমি বুঝি না। একদম ছোট থাকতে হোমোসেক্সুয়ালিটিকে যে বাংলাদেশে ক্রিমিনালাইজড করা ছিল তা আমি জানতাম না, কিন্তু অনেক ধরণের সামাজিক বৈষম্য সম্পর্কে বেশ সচেতন ছিলাম। বাংলাদেশের সমাজ কতটা বাইনারি, কতটা হেটোরোনরমাটিভ, কতটা লিঙ্গ বৈষম্যমূলক ছিল সেগুলা নিয়ে সচেতন ছিলাম। এবং এর মধ্যে ঠিক মানিয়ে নিতে পারিনি । তুমি জানো যে বাংলাদেশের সমাজ কতটা রিলিজিয়াস। যেমন, শুক্রবার দিনে খুতবার সময়ে মসজিদের মাইকগুলো যেনো ফেটে পড়ত। তোমার তো এভাবে প্রচার করার দরকার নাই! আচ্ছা, এটা যার যার ব্যক্তিগত ধর্মীয় স্বাধীনতা সেটা মানলাম, কিন্তু তোমার তো খুতবার মধ্যে এটা প্রচার করার দরকার নাই যে নারীরাই জাহান্নামের প্রথম বাসিন্দা, এরকম অনেক কিছু, অনেক টক্সিক কথাবার্তা বলা হত… আমার জেন্ডার আইডেন্টিটি এবং সেক্সুয়ালিটির (সেক্সুয়াল অরিয়েন্টশন আমার এখানকার আমেরিকার জীবনে এসে গুরুত্বপূর্ন হয়ে উঠছে) ইস্যু বাদেই ধর্মের সাথে আমার একটা বাজে সম্পর্ক ছিল কারন নিজেকে কখনো আমি নাস্তিক ছাড়া অন্য কিছু এমনটা ভাবিনি... এরপর, বাংলাদেশে নাস্তিক এবং সেক্যুলারিস্ট, ব্লগারদের উপর সামজিক নির্যাতন ও খুনের যে মহোৎসব শুরু হলো সেটা নিশ্চয়ই তোমার মনে আছে। এটাও ঘড়ির কাঁটা ঘোরার মতই ছিল, যেমন - কয়েক মাস পর পরই পত্রিকা খুললেই দেখবা যে কোনো একজনকে ইসলামী অনুভূতিতে আঘাত দিছে বলে প্রকাশ্য দিনের আলোয় খুন করা হইছে। এগুলা কিন্তু কোনো র্যান্ডম খুন ছিল না। এই ব্লগারদের নামের তালিকা করা হয়েছিল। এইগুলা খুনীদের প্ল্যান করে করা কাজ। এইগুলা সিস্টেমেটিক ছিল। একটা ভয় ছড়ানোর জন্যই এগুলার ডিজাইন করা হয়েছিল। এবং আমি... আমার মনে হয় জীবনে প্রথমবারের মত সত্যি অনেক ভয় পেয়েছিলাম।

None Of Your Business

I'm a very private person. It's [gender and sexual orientation etc.] no one else's business, so I didn't exactly go out of my way to broadcast it or anything. I mean, it wasn't just my sexual orientation or gender identity. I'm non binary and I go by they/them. I didn't broadcast that. It was just a lot of other things about myself. I really just talked about myself. My sexuality, my identity were in that box of things in my mind that I just did not talk to people about, right? Alongside religion. I happened to be an atheist as well.

আমি একটু প্রাইভেট টাইপের মানুষ। এগুলা [জেন্ডার, সেক্সুয়ালিটি] অন্য কারো মাথা ঘামানোর বিষয় না, তাই আমি এগুলা ব্রডকাস্ট বা এমন কিছু করতে যাই নাই। মানে, এইটা শুধু আমার সেক্সুয়াল অরিয়েন্টশন, লিঙ্গ পরিচয়ের ব্যাপার না। আমি নন-বাইনারি, আমার জেন্ডার সর্বনাম সে বা তারা। আমি এটা ব্রডকাস্ট করি নাই। এটা আমার সাথে সম্পর্কিত বাকি অনেক কিছুর মতই। আমি শুধু আমার সম্পর্কে বলেছি। আমার সেক্সুয়ালিটি, আমার পরিচয় নিয়ে আমি আলাদা করে মানুষের সাথে কথা বলিনি। যেমনটা ধর্ম নিয়ে বা আমার নাস্তিকতা বিষয়েও বলি না।

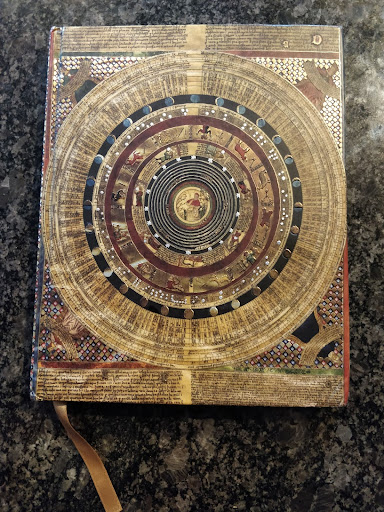

Artifacts