On April 22, 1913, two brothers – Sant and Tulsi Ram – landed in San Francisco via the S.S. Mongolia, after leaving their home in Ludhiana, Punjab. Like many of the Asian immigrants who came to the U.S. through the Pacific, the brothers were detained in Angel Island Immigration Station in San Francisco Bay, and kept there for further inspection. Tulsi Ram, 18, and his brother Sant Ram, 20, were planning to go to Pittsburgh to pursue their studies (agriculture for Tulsi, and mechanical engineering for Sant). Following a brief interrogation by immigration officials, Tulsi Ram was admitted into the country. The verdict on his brother Sant, on the other hand, was that he be "excluded and deported."

The difference in Sant Ram’s case was that he was "afflicted with Uncinariasis, a dangerous contagious disease," known commonly as hookworm. The inspectors provided the caveat that only if “hospital treatment is applied for and granted in this case, and a cure is effected” would Sant Ram be admissible under immigration law. This was not a rare scenario. In their study of Angel Island, Erika Lee and Judy Yung explain that the presence of hookworm had become a common justification for excluding South Asians; Angel Island’s chief medical officer, for example, discovered hookworm in "65 percent of South Asian immigrants applying for admission."1 Treatment for hookworm could cost up to $50, and if detainees could not foot the bill, they were deported. Sant Ram, it turns out, might have been able to pay for his treatment. But others -- like Asa Singh, Sukumar Chatterji, and Sohn Singh (also in the SAADA archive) -- may not have been that fortunate.

In the early 20th century, hookworm infection had become part of the lexicon that immigration officials used to describe the South Asian migrant’s body. The transcript from the 1914 Congressional hearing on "Hindu Immigration" came with an addendum on "Hookworm Inspection," detailing the numbers of infected Hindu laborers worldwide. The report estimated that “60 to 80 per cent of the total population of India [was] infected,” before discussing the outward spread of "Indian coolies" in Jamaica, Assam, Ceylon, South Africa, British and Dutch Guiana, and Malay. The report suggests that the Hindus in California had now formed a “center from which the infection is spreading in that State.”

Why was hookworm so reviled? For starters, it was (and is) a nasty parasite, causing anemia and other symptoms in its host. But historically, infection by hookworm also fit a convenient script that reinforced the various threats that Asian immigrants were imagined to pose.2 Reports linked uncinariasis to low work productivity, as well as producing "retarding effects on education" and a "cumulative handicap to the development of […] all things that make for civilization." Historian Nayan Shah takes up this issue in his study Contagious Divides, describing how hookworm was commonly referred to as the "germ of laziness."3 The discourse around hookworm infections then contributed not only to the perception of the South Asian as a contagion, but also as an unproductive member of society. This further underscored another common cause for exclusion around this time: the assessment that an immigrant would become a "public charge," unable to sustain him or herself, and thus leeching the state of its resources.

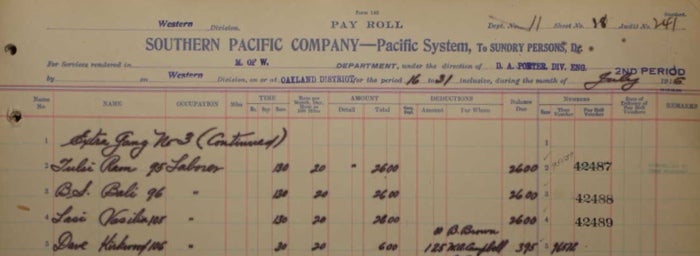

What happened to the Ram brothers? A payroll record from the Southern Pacific Company indicates that someone by the name of Tulsi Ram was employed by the railroads in July 1916. Decades later, a census report records a Tulsi Ram residing in the U.S., working in a sawmill in Grays Harbor, Washington.4 As for his brother, despite the initial ruling that Sant Ram be excluded, he appears to have been admitted after receiving treatment on May 17, 1913, nearly a month after first arriving on Angel Island.

[Explore our collection of case files for South Asians detained on Angel Island here. These files were digitized from the National Archives at San Francisco.]

1. Lee, Erika and Judy Yung. Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. 152.

2. Marcus, Alan. "Physicians Open a Can of Worms: American Nationality and Hookworm in the United States, 1893-1909." American Studies. 30.2 (1989): 103-121. Marcus traces how at various points from the late 19th to early 20th century, hookworm was associated with poor whites, Southerners, and lower-class European immigrants, "inhabitants of the tropics," Native Americans, and eventually African Americans. Marcus suggests that "hookworm persisted as a problem of American nationality."

3. Shah, Nayan. Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. 190.

4. The 1930 census report and Southern Pacific Company payroll report were retrieved from Ancestry.com.

Manan Desai teaches at Syracuse University and serves on the Board of Directors for the South Asian American Digital Archive.